The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is one of the most important organelles found in eukaryotic cells, playing a vital role in keeping the cell alive and functioning properly.

Often described as the cell’s internal factory and transport system, the endoplasmic reticulum is responsible for producing, processing, and moving essential molecules throughout the cell.

It is a large network of membranes that extends from the nucleus and spreads across the cytoplasm, connecting different parts of the cell into a coordinated system.

Understanding what the endoplasmic reticulum does is essential for students of biology because many critical cellular processes depend on it.

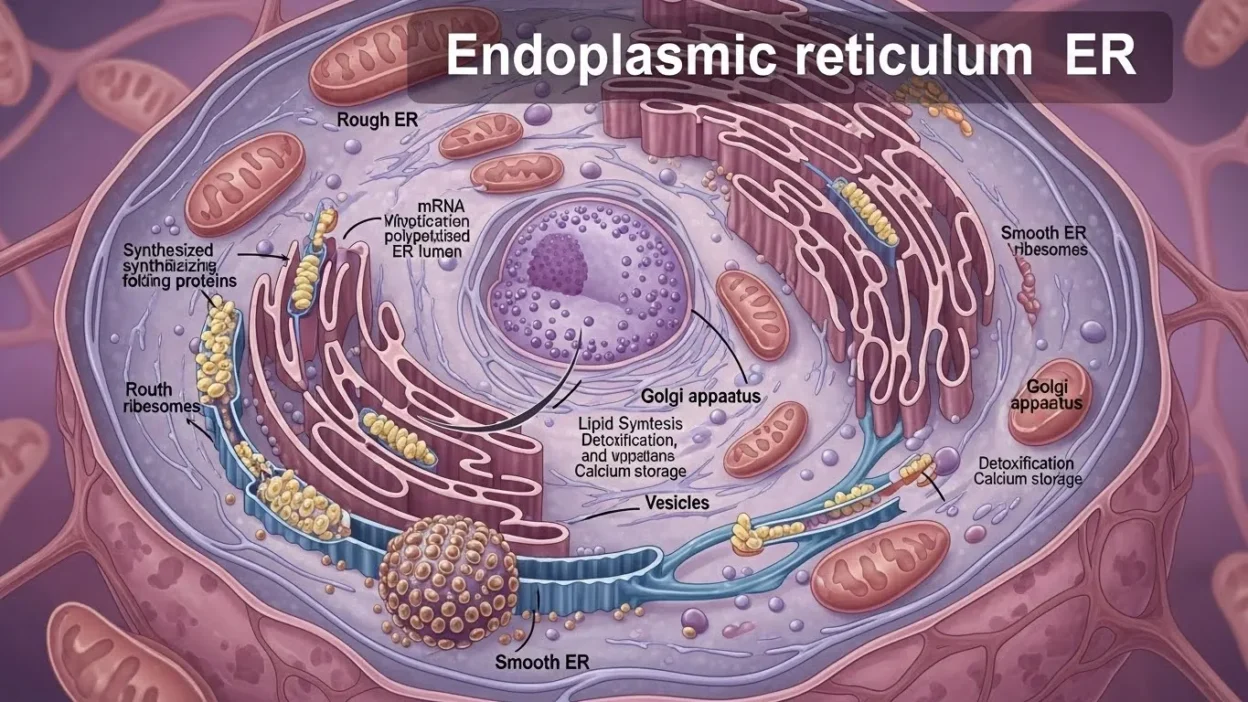

The ER exists in two main forms:

the rough endoplasmic reticulum, which helps in protein synthesis, and the smooth endoplasmic reticulum, which is involved in lipid production, detoxification, and calcium storage.

Together, these two types allow the cell to grow, adapt, and respond to its environment.

In this article, we will explore the structure, functions, and importance of the endoplasmic reticulum in detail.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a vital organelle that acts as the cell’s production and transport hub. In simple terms, the ER produces, processes, and transports proteins and lipids, ensuring that they reach the correct destinations within the cell.

In animal cells, the rough ER specializes in protein synthesis for secretion and membrane insertion, while the smooth ER focuses on lipid production, detoxification, and calcium storage.

By coordinating these functions, the ER keeps the cell organized, supports metabolism, and ensures overall survival. Without the ER, many essential processes in the cell, including protein folding and lipid supply, would be severely disrupted.

What Is the Endoplasmic Reticulum?

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a membrane-bound organelle found in all eukaryotic cells, including animal and plant cells. It is made up of a complex network of flattened sacs, folded membranes, and tubular structures that extend throughout the cytoplasm. This extensive structure allows the ER to interact closely with other organelles and efficiently carry out its many functions. The membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum is continuous with the nuclear envelope, which highlights its close relationship with the nucleus and genetic material of the cell.

In simple terms, the endoplasmic reticulum acts as a manufacturing and transport system inside the cell. It is responsible for producing important biological molecules, such as proteins and lipids, and ensuring they are properly processed before being delivered to their final destinations. The internal space of the ER, known as the ER lumen, provides a controlled environment where newly made proteins can fold into their correct shapes.

The endoplasmic reticulum is divided into two main regions based on structure and function. The rough endoplasmic reticulum has ribosomes attached to its surface, giving it a rough appearance under a microscope and making it the primary site for protein synthesis. In contrast, the smooth endoplasmic reticulum lacks ribosomes and is involved in lipid synthesis, detoxification of harmful substances, and calcium ion storage. Together, these two regions allow the ER to support a wide range of essential cellular activities.

Structure of the Endoplasmic Reticulum

The structure of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is uniquely designed to support its diverse functions within the cell. It consists of an interconnected system of membranes that form flattened sacs called cisternae, along with branching tubules and vesicles. This extensive membrane network spreads throughout the cytoplasm, creating a large surface area that allows the ER to carry out complex biochemical processes efficiently. One of the defining features of the ER is that its outer membrane is directly connected to the nuclear envelope, enabling close coordination between protein synthesis and genetic instructions from the nucleus.

The ER membrane is composed of a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins that serve as enzymes, receptors, and transport channels. These membrane proteins are essential for the movement of molecules into and out of the ER and for carrying out chemical reactions. Inside the ER is the lumen, a fluid-filled space that plays a crucial role in protein folding and modification. The lumen provides a controlled environment where newly synthesized proteins can form proper three-dimensional structures with the help of specialized enzymes and chaperone proteins.

Structurally, the endoplasmic reticulum can appear different depending on the cell type and its activity level. Cells that produce large amounts of proteins, such as plasma cells, have an extensive rough ER, while cells involved in detoxification and lipid metabolism, like liver cells, contain a well-developed smooth ER. This structural adaptability allows the endoplasmic reticulum to meet the specific functional demands of different cells.

Types of Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is divided into two main types based on its structure and function: the rough endoplasmic reticulum (rough ER) and the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (smooth ER). Although both types are part of the same continuous membrane system, each plays a distinct role in maintaining normal cellular activity.

The rough endoplasmic reticulum is characterized by the presence of ribosomes attached to its outer surface. These ribosomes give it a rough appearance when viewed under a microscope. The rough ER is primarily responsible for protein synthesis, especially proteins that are destined for secretion, insertion into the cell membrane, or transport to other organelles. As proteins are synthesized, they enter the ER lumen, where they begin the process of folding into their correct shapes. The rough ER also plays a role in modifying proteins and packaging them into transport vesicles for delivery to the Golgi apparatus.

In contrast, the smooth endoplasmic reticulum lacks ribosomes and has a smooth, tubular appearance. Its functions are mainly related to lipid metabolism and cellular detoxification. The smooth ER synthesizes lipids, including phospholipids and steroid hormones, which are essential components of cell membranes. It also helps detoxify harmful substances such as drugs and poisons, particularly in liver cells. Additionally, the smooth ER is involved in calcium ion storage and release, which is especially important in muscle cells for proper contraction. Together, the rough and smooth ER ensure efficient cellular production, regulation, and transport.

Functions of the Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) performs several essential functions that are critical for the survival and proper functioning of the cell. One of its primary roles is protein synthesis and processing. In the rough endoplasmic reticulum, ribosomes translate genetic instructions into protein chains. These newly formed proteins enter the ER lumen, where they are folded into their correct three-dimensional structures and checked for quality. Properly folded proteins are then packaged into transport vesicles and sent to the Golgi apparatus for further modification and distribution.

Another important function of the ER is lipid synthesis. The smooth endoplasmic reticulum produces phospholipids and cholesterol, which are key components of cellular membranes. It also synthesizes steroid hormones, making it especially important in endocrine tissues such as the adrenal glands and ovaries. By supplying lipids, the ER helps maintain membrane integrity and supports cell growth and repair.

The endoplasmic reticulum also plays a major role in detoxification. In liver cells, enzymes within the smooth ER break down harmful substances, including drugs and toxins, into less harmful compounds that can be removed from the body. This detoxification process protects cells and tissues from chemical damage.

In addition, the ER regulates calcium ion storage and signaling. Specialized regions of the smooth ER store calcium ions and release them when needed for processes such as muscle contraction, nerve signaling, and cell communication. Through these combined functions, the endoplasmic reticulum acts as a central hub for cellular metabolism, regulation, and transport.

Endoplasmic Reticulum and Other Cell Organelles

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) does not function in isolation; instead, it works closely with other cell organelles to maintain efficient cellular organization and activity. One of its most important relationships is with ribosomes. Ribosomes attached to the rough endoplasmic reticulum synthesize proteins based on instructions from messenger RNA. This close association ensures that proteins destined for secretion or membrane insertion enter the ER immediately after being formed.

The ER also has a strong functional connection with the Golgi apparatus. After proteins and lipids are synthesized and partially processed in the ER, they are packaged into small transport vesicles. These vesicles move from the ER to the Golgi apparatus, where the molecules are further modified, sorted, and labeled before being sent to their final destinations inside or outside the cell. This ER–Golgi transport system is essential for proper protein delivery and cellular communication.

In addition, the endoplasmic reticulum interacts with mitochondria, the energy-producing organelles of the cell. These interactions help regulate lipid exchange and calcium signaling between the two structures, which is important for metabolism and energy balance. The ER also contributes to the formation of new membranes by supplying lipids to other organelles, helping them grow and maintain their structure.

Through these interactions, the endoplasmic reticulum acts as a central coordinating network within the cell. By linking protein production, lipid synthesis, and intracellular transport, the ER ensures that all organelles work together smoothly to support cell survival and function.

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Quality Control

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) plays a critical role in maintaining protein quality within the cell. During normal conditions, proteins synthesized in the rough ER are carefully folded into their correct shapes with the help of specialized enzymes and molecular chaperones. However, when the ER becomes overwhelmed by an excess of newly made or misfolded proteins, a condition known as endoplasmic reticulum stress occurs. This stress disrupts normal cellular function and can threaten cell survival if not properly managed.

To cope with ER stress, cells activate a protective mechanism called the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR works by temporarily slowing down protein synthesis, increasing the production of chaperone proteins that assist in folding, and enhancing the removal of incorrectly folded proteins. These responses help restore balance within the ER and protect the cell from damage. If the stress is mild or short-lived, the cell can usually recover successfully.

However, prolonged or severe ER stress can have serious consequences. When the unfolded protein response fails to restore normal conditions, it can trigger programmed cell death, also known as apoptosis. This process prevents damaged cells from harming surrounding tissues. Persistent ER stress has been linked to several diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and certain types of cancer.

By maintaining strict quality control over protein production and responding to cellular stress, the endoplasmic reticulum helps ensure that only properly functioning proteins move through the cell. This quality control system highlights the ER’s vital role in preserving cellular health and preventing disease.

Diseases Related to Endoplasmic Reticulum Dysfunction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is essential for proper protein folding, lipid synthesis, and cellular homeostasis, so its malfunction can have serious consequences for human health. When the ER is stressed or unable to properly fold proteins, it triggers a chain reaction that affects cell survival. This dysfunction is linked to several diseases, particularly those involving chronic cellular stress or protein misfolding.

One major category of ER-related diseases is neurodegenerative disorders. Conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease are associated with the accumulation of misfolded proteins in neurons. ER stress contributes to neuronal damage and cell death, which leads to the progressive loss of brain function observed in these diseases.

Diabetes is another condition linked to ER dysfunction. In pancreatic beta cells, which produce insulin, prolonged ER stress can impair insulin production and secretion. This disruption contributes to high blood sugar levels and the progression of type 2 diabetes. Similarly, cardiovascular diseases may involve ER stress in heart cells, affecting their ability to function properly under stress.

ER malfunction is also implicated in cancer. Some cancer cells exploit the unfolded protein response to survive in stressful conditions, promoting tumor growth and resistance to chemotherapy. In addition, rare genetic disorders, such as certain types of congenital muscular dystrophy, result from mutations affecting ER proteins, leading to severe developmental issues.

Overall, the connection between ER dysfunction and disease highlights the importance of this organelle in maintaining cellular health. By understanding its role, researchers can develop therapies aimed at reducing ER stress and restoring proper cell function.

Endoplasmic Reticulum in Specialized Cells

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) adapts its structure and function to meet the specific demands of different cell types, making it a versatile and essential organelle in specialized cells. For example, in liver cells (hepatocytes), the smooth ER is highly developed to perform detoxification of drugs and harmful substances. These cells rely on the ER’s enzymes to break down toxins into compounds that can be safely removed from the body, maintaining overall health.

In muscle cells, specialized regions of the ER, called the sarcoplasmic reticulum, store and release calcium ions. Calcium is critical for muscle contraction, and the sarcoplasmic reticulum ensures that muscle cells respond quickly and efficiently to nerve signals. Without this function, muscle movement and coordination would be severely impaired.

Secretory cells, such as pancreatic cells or plasma cells that produce antibodies, have an extensive rough ER to meet their high protein production needs. The rough ER in these cells synthesizes and folds large quantities of proteins, which are then transported to the Golgi apparatus for modification and secretion. This allows the cells to maintain their essential roles in metabolism, immunity, and hormone production.

Even in plant cells, the ER is important for producing lipids, proteins, and cell wall components. It works closely with other organelles, such as the Golgi apparatus and chloroplasts, to support plant growth and energy production.

Overall, the ER’s ability to adapt to different cellular needs highlights its critical role in specialized functions, ensuring that each cell type can efficiently carry out its unique tasks within the organism.

Endoplasmic Reticulum in Plant vs. Animal Cells

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a crucial organelle in both plant and animal cells, but its roles and structure can differ slightly depending on the type of cell. In both cases, the ER forms a network of membranes that connects to the nuclear envelope, supporting protein synthesis, lipid production, and intracellular transport. However, the specific needs of plant and animal cells influence how the ER develops and functions.

In animal cells, the ER is heavily involved in protein processing and secretion, lipid metabolism, and detoxification. For example, liver cells in animals rely on the smooth ER to metabolize toxins and drugs. Muscle cells contain specialized smooth ER, known as the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which stores calcium ions critical for muscle contraction. Secretory cells, such as those in the pancreas or immune system, contain an extensive rough ER to handle high rates of protein production.

In plant cells, the ER also participates in protein and lipid synthesis but has additional roles. It helps in the production of components for the cell wall, such as polysaccharides, and interacts with the Golgi apparatus and vacuoles for transporting these materials. The ER is also closely associated with chloroplasts, helping to regulate lipid transfer and energy metabolism required for photosynthesis. Plant cells do not require detoxification of the same substances as liver cells, so their smooth ER is less specialized in this function.

Despite these differences, the ER in both plant and animal cells remains essential for cellular organization, metabolism, and survival, adapting its structure to meet the specific demands of each cell type.

In plant cells, the ER not only produces proteins and lipids but also contributes to cell wall formation and interacts closely with chloroplasts to regulate energy and lipid transfer needed for photosynthesis. Animal cells rely on the ER for protein secretion, lipid metabolism, and detoxification, with specialized regions like the sarcoplasmic reticulum storing calcium for muscle contraction. Overall, while both plant and animal cells depend on the ER for fundamental cellular functions, each adapts the ER’s role to meet its specific needs.

Importance of the Endoplasmic Reticulum in Cell Survival

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is vital for cell survival because it performs multiple functions that keep the cell organized, efficient, and capable of responding to internal and external changes. One of the ER’s key contributions is protein synthesis and quality control. Proteins produced in the rough ER are properly folded, modified, and packaged for transport. This ensures that the cell has the right proteins for structural support, enzymatic activity, and signaling, which are essential for maintaining normal cellular functions.

Another critical role of the ER is lipid and membrane production. The smooth ER synthesizes lipids, phospholipids, and cholesterol that form the cell’s membranes. These lipids are not only structural components but also help in cell signaling and communication. Without a functional ER, cells would struggle to maintain their membranes, leading to cellular instability and dysfunction.

The ER also supports detoxification and metabolic balance, particularly in liver cells, where it neutralizes toxins and drugs. Additionally, the ER regulates calcium ion storage and release, which is crucial for processes such as muscle contraction, nerve signaling, and enzyme activation. This allows cells to react quickly to environmental and internal signals.

Finally, the ER is central to cellular stress management. By detecting misfolded proteins and activating the unfolded protein response (UPR), the ER protects the cell from damage and apoptosis. Overall, the ER’s wide range of functions ensures that the cell remains healthy, adaptable, and capable of survival in varying conditions. It is truly the cell’s control center for production, regulation, and communication.

Simple Explanation of the Endoplasmic Reticulum for Students

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) can be thought of as the cell’s factory and transport system, making it easier to understand for students and beginners in biology. Imagine a large factory where raw materials are processed, products are assembled, and finished goods are packaged for delivery—this is similar to how the ER works inside the cell. It takes instructions from the nucleus, produces proteins and lipids, and ensures they are correctly folded and sent to where they are needed.

The ER has two main types: the rough ER and the smooth ER. The rough ER has ribosomes on its surface, which are like tiny machines that produce proteins. These proteins are then folded and modified inside the ER, preparing them for use within the cell or for export outside the cell. The smooth ER, on the other hand, doesn’t have ribosomes. It focuses on lipid production, detoxifying harmful substances, and storing calcium ions, which are important for processes like muscle contraction.

Another way to think of the ER is as a delivery network. Just like a post office sorts and sends packages to the correct addresses, the ER ensures proteins and lipids are transported to the Golgi apparatus, membranes, or other organelles. Without the ER, the cell would lose its organization, and essential molecules would not reach their destinations.

In short, the ER is a multi-functional hub in the cell, handling production, storage, and transport. Understanding its functions helps students grasp how cells maintain life, grow, and respond to changes in their environment.

For kids and beginners, the ER can be thought of as the cell’s factory and delivery system. The rough ER, with its tiny ribosome “machines,” makes proteins, while the smooth ER produces fats and detoxifies harmful substances. Just like a factory sorts and delivers products to the right place, the ER ensures proteins and lipids reach their destinations in the cell, keeping everything running smoothly.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About

1. What does the endoplasmic reticulum do in a cell?

The ER is a network of membranes that produces, processes, and transports proteins and lipids. It also stores calcium ions and helps detoxify harmful substances. Essentially, it acts as the cell’s factory and transport system.

2. What is the difference between rough ER and smooth ER?

The rough ER has ribosomes attached to its surface, giving it a “rough” appearance, and is primarily responsible for protein synthesis. The smooth ER lacks ribosomes and is involved in lipid production, detoxification, and calcium storage.

3. What does the endoplasmic reticulum do in cells?

A: The ER produces and transports proteins and lipids, stores calcium, and detoxifies harmful substances, making it essential for the health and function of eukaryotic cells.

4. What does the endoplasmic reticulum do in a city?

A: While “city” is not a scientific term in biology, think of the ER like a city’s factory and delivery system—producing goods (proteins and lipids) and sending them to where they are needed, ensuring smooth operation.

5. What does the endoplasmic reticulum do quizlet?

According to Quizlet and educational resources, the ER is the cell’s network for making and transporting proteins and lipids, regulating calcium, and detoxifying substances.

6. Is the endoplasmic reticulum found in all cells?

No, the ER is present only in eukaryotic cells (cells with a nucleus). It is not found in prokaryotic cells, such as bacteria.

7. What happens if the ER stops working?

If the ER malfunctions, proteins may fold incorrectly, lipids may not be produced properly, and calcium balance may be disrupted. This can lead to ER stress, triggering cell damage or apoptosis, and is linked to diseases like Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and certain cancers.

8. Why is the ER important for cellular survival?

The ER ensures that proteins and lipids are correctly produced and transported, helps detoxify harmful substances, and maintains calcium levels. Without it, cells would lose organization and fail to function, ultimately threatening survival.

9. How does the ER work with other organelles?

The ER works closely with the Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and ribosomes to transport molecules, regulate energy and metabolism, and maintain overall cellular function.

Conclusion:

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is one of the most vital organelles in eukaryotic cells, serving as a central hub for production, transport, and regulation.

By forming a continuous network of membranes connected to the nucleus, the ER ensures that proteins and lipids are synthesized, properly folded, and directed to their correct destinations within the cell.

The rough ER, with its ribosomes, focuses on protein production, while the smooth ER is specialized in lipid synthesis, detoxification, and calcium storage. Together, these two types of ER work in harmony to maintain cellular balance.

The ER’s importance extends beyond basic cellular functions. It actively manages ER stress by detecting misfolded proteins and triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) to restore normal conditions.

This quality control system prevents cell damage and supports survival under stressful conditions.

When the ER fails to function properly, it can contribute to serious diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and certain cancers.

During meaning specialized cells, such as liver cells, muscle cells, and secretory cells, the ER adapts to meet specific demands, highlighting its versatility and critical role in overall organismal health.

In both plant and animal cells, the ER ensures proper growth, metabolism, and response to environmental changes.

In summary, the endoplasmic reticulum is much more than a cellular structure; it is the cell’s factory, transport system, and quality control center.

Understanding its functions helps students, researchers, and healthcare professionals appreciate how cells sustain life, respond to stress, and contribute to health and disease.

The ER truly exemplifies the intricate and highly organized nature of cellular life.

Discover More Articles:

- What Does Your Liver Do? Discover Its Amazing Functions

- What Does the Cytoplasm Do? Key Functions Explained

- What Does Fiber Do? Benefits for Your Body Explained

The author behind RiddleBurst.com loves creating fun, clever, and unique riddles for all ages. Their goal is to challenge minds, bring smiles, and make learning through riddles both engaging and enjoyable.